Luca Campigotto, Iconic China

Seeing Is Believing

Monograph Essay for Iconic China, Luca Campigotto (Damiani, 2017)

Did Marco Polo actually travel as far as to China? Who knows? But we are left with this statement or at least the Italian equivalent: «I did not tell half of what I saw for I knew I would not be believed».

Luca Campigotto could probably make the same remark after his extended photographic journey for his newest project Iconic China , and like his predecessor, he would also offer it in Italian.

He opens with “China Past”, gorgeous vistas of some traditional Chinese landscapes like the Great Wall, the surreal limestone mountains next to the River Li and the terra-cotta warriors in Xian. This is standard fare. But we have a good guide in Campigotto. He is one of the great landscape photographers at work today as witnessed in his earlier books Theatres of War (2015), Gotham City (2012), My Wild Places (2011) and Venice: The City by Night (2006).

Then, like that meandering Chinese river, he changes course abruptly and brings us into “China Present”. The Present takes the viewer into the city, and we have never seen a place like this before. We definitely need him as our guide.

The Shanghai Bund riverfront has been a visually fascinating site throughout the history of photography. It’s impossible to be prepared for what it looks like now, particularly in these photographs. Similarly Beijing and Hong Kong are almost unrecognizable even from the days when China opened to the West. There is a smart pairing of a triad of small mountains in the Yangshuo countryside (page 23) reappearing as a set of lit up office buildings in Beijing (page 53). Emerging mega-city Chongqing looks like it was built overnight.

It is not the size or design or these new buildings that are so striking but rather the color and the quality of the light. Campigotto is known for his mountains in the day and cityscapes at night, not the light itself.

Campigotto skies are always memorable, whether at night over cities like New York or Venice or during the day over rocky terrain in his My Wild Places or Theatres of War . The Chinese skies, by comparison, are colorless and neutral; they act like shiny steel backgrounds reflecting the sheen of these alien-looking hues. The rivers do the same thing.

The color is managed impressively. There is a Hong Kong waterfront view (page 65) with very little information in it. Opposing towers face off across a body of water with some unidentifiable submerged somethings in the middle foreground, but the sky is filled with an aurora of complementary color, a light show of setting sun and pollution.

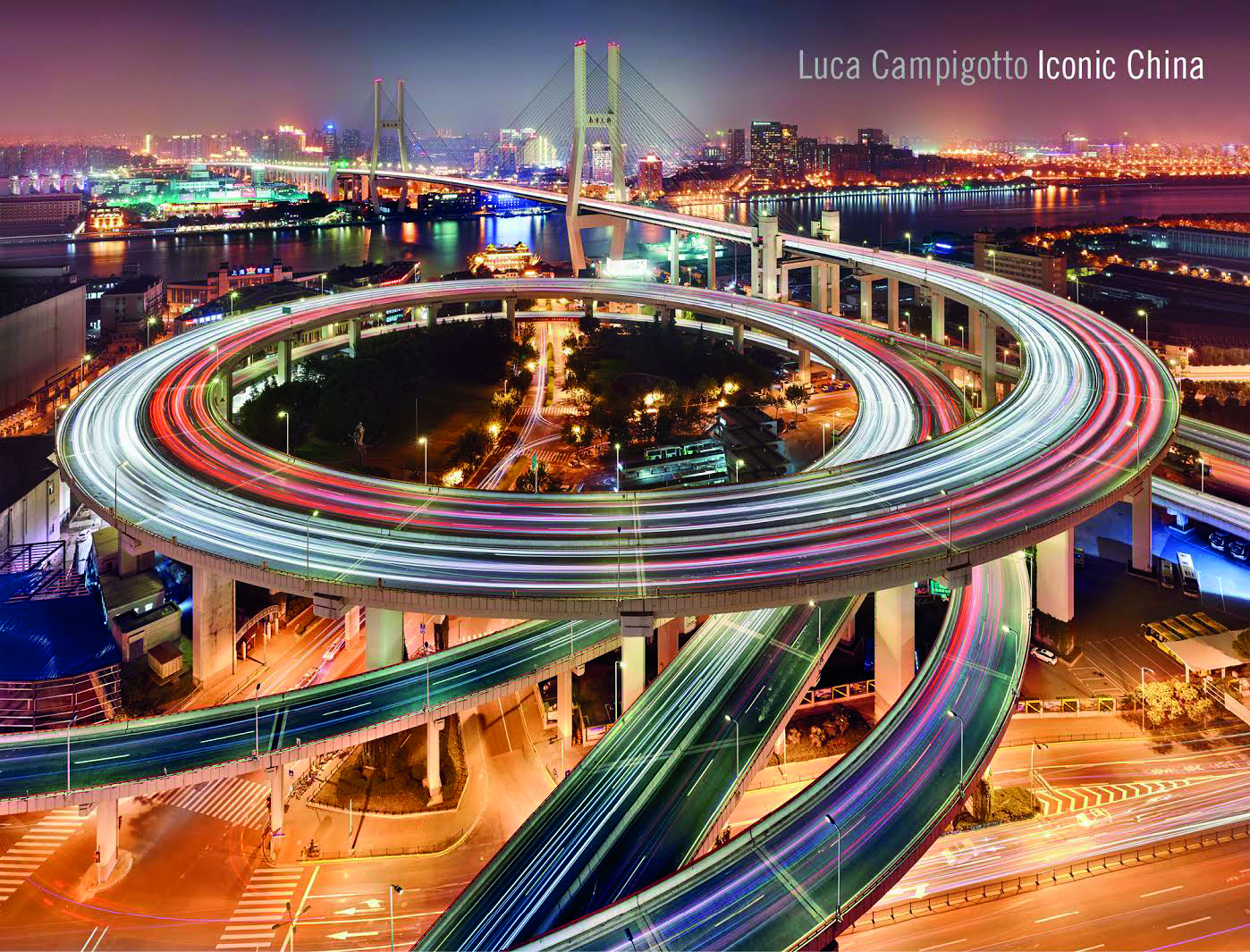

There are a couple of swirling Shanghai roadway images that are exhilarating, one (page 57) looks like a spinning top. The long time exposure reveals looping ribbons of headlights, like an electric coil. Another matrix of vectors (page 59) is a vibrant yellow, an unlikely color in the night.

A Hong Kong housing project series captures a crazy urban energy without showing masses of people. The palette is still filled with garish, gaudy, lurid, ghostly colors, but here the artist finesses a couple of surprises. By shooting straight up the side of building he finds an unexpected and jumbled topography suggesting the mad, crowded hustle and bustle of the city (page 66-67). He then appears to show us the same facade from head on (page 71); it’s

the same and not the same. In two others (page 69, 73) he cuts into the mass with rectangles of negative space, salmon pink night skies perfectly framed by new buildings, sweetly and unconsciously referencing a classic Beaumont Newhall, Chase National Bank, New York , 1928.

Campigotto does know his photo history. He is a lover of the great large format works by Carleton Watkins, and then Timothy O’Sullivan, and the photographers of the Grand Tour: Francis Frith, the Beato brothers, Roger Fenton. There exists a unique 13 part panorama of 1873 Shanghai by Henry Cammidge, and as stunning as that may be, Campigotto’s work looks as exotic to us today as did its 19th Century predecessors.

In the essay A Timeless Place written for his 2006 project Venicexposed, Campigotto observed something about his black and white photography. «The photographs bring the unforgettable to life. I love them because they give the illusion that we may find once again the things we have lost, or that we never possessed. A last glance can take the thing that we fear we may never see again and transform it into an icon. In the persuasive unfaithfulness of black and white, the dream is premeditated. Photography may well be nostalgia’s greatest tool».

If black and white is the tool for remembrance, it may be that color in photography serves to help us to look into the future.

Hong Kong looks like, well, Hong Kong, like a “Blade Runner” dystopian sprawl but real, the city as video game. Is it funny to describe all of this as “dis-orienting”? The colors are electric or radioactive. It is as if Syd Mead, the futurist designer for that 1980’s film, became the city planner. Batty, the Rutger Hauer replicant in that movie even references Marco Polo with the remark, «I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe».

The artist says that conditions were rough for him in China, not knowing the language or the terrain, but finding his way, trusting his instincts and experience has yielded impressive and thoughtful work. He is admiring of the American photographer, Robert Adams, who like Campigotto is a good writer. «One does not for long wrestle a view camera in the wind and heat and cold just to illustrate a philosophy. The thing that keeps you scrambling over the rocks, risking snakes, and swatting at the flies is the view. It is only your enjoyment of and commitment to what you see, not to what you rationally understand, that balances the otherwise absurd investment of labor».*

Campigotto captures the wonders of these brave new worlds, Chinas Present and Past, where “Seeing is Believing” or, in Italian,“Vedere per Credere”.

* Robert Adams, Introduction to The American Space: Meaning in Nineteenth-Century Landscape Photography, Wesleyan University Press, 1983