Rocket Man

Prologue to First Fleet: NASA Space Shuttle Program 1981-1986, John A. Chakeres, 2018

And I think it's gonna be a long long time

Till touch down brings me round again to find

I'm not the man they think I am at home

Oh no, no, no, I'm a rocket man

Rocket man burning out his fuse up here alone . . .[i]

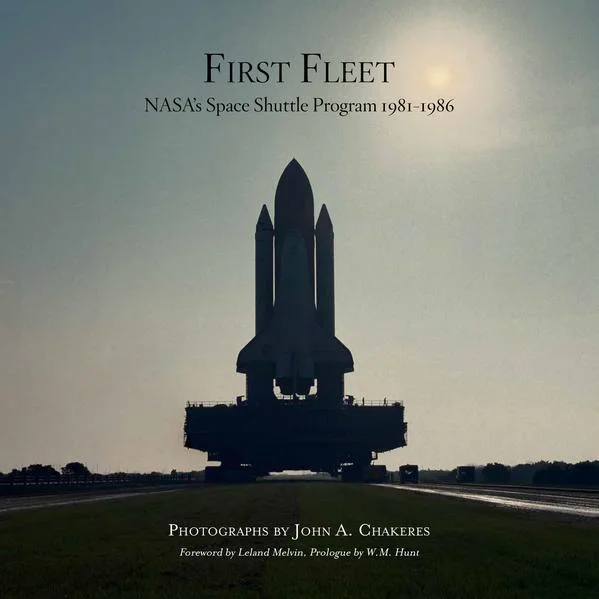

John A. Chakeres is a Rocket Man, and First Fleet: NASA’s Space Shuttle Program 1981–1986 is his “message in a bottle” love story.

Space travel has been the intoxicating stuff of science fiction since the late-nineteenth century when Jules Verne wrote his novels From the Earth to the Moon (1865) and Around the Moon (1870). H. G. Wells's The First Men in the Moon (1901) was probably the basis for Frenchman George Méliès' early film Le Voyage dans la Lune (1902), the title of which translates as A Trip to the Moon. This cleared the way for twentieth-century characters like Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, and, even later, Luke Skywalker.

Reality caught up with fiction on October 4, 1957, when the Russians launched Sputnik, the first Earth-orbiting satellite. This event was both chilling and exhilarating. Soon enough dogs, monkeys, and then men went off into space. The first human to orbit the earth was Yuri Gagarin, on April 12, 1961. A month later, in May, Alan Shepard was the first U.S. astronaut to make a suborbital flight, and a year after that, on February 20, 1962, NASA astronaut John Glenn orbited the earth three times.

In 1966 Star Trek and the “final frontier” aired on television, but man had indeed already gone “where no man has gone before.”[ii]

Initially, these real space programs and actual missions had mythological names like Apollo and Mercury. These gave way to Challenger, Discovery, and Endeavour, named for the historic ships that pioneered world navigation. Look for Chakeres’ portraits of Columbia OV-102, Challenger OV-99, Discovery OV-103, and Atlantis OV-104 with their handsome, god-like, monolithic “otherness.”

The United States prevailed in the 1960s space race with six Apollo missions to the moon. Astronauts Virgil "Gus" Grissom, Edward White, and Roger Chaffee were killed in a launch-pad fire in 1967, but Neil Armstrong and Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin successfully landed on the moon on July 20, 1969.

Congress pulled the plug on the program and the first era of human space exploration closed when the Apollo missions ended in 1972. The space program resumed when the Columbia took off on April 12, 1981—the first flight of NASA’s Space Shuttle program.

Some boys like to build model airplanes and rockets. In that way, fifty years ago, John Chakeres fell in love with travel into space. He became obsessed, looking at pictures in Life magazine, staying home from school to watch launches on TV and setting up his father’s Rolleiflex camera in front of it to photograph them. He built a darkroom and learned how to print. He studied photography in college and ultimately saw an opportunity to actually photograph the Space Shuttle himself. He got permission from NASA to be on site for takeoffs at the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral Florida.

Between 1981 and 1986 Chakeres devoted himself to photographing the space shuttle program, even inventing remote triggers for motor-driven cameras to avoid the rocket thrust.

These pictures were fashioned with the single-mindedness of a nine-year-old model maker. Chakeres’ awe of these gigantic, streamlined craft with their sharp modernity is evident. His affection and admiration—obsession—are visceral. He looks closely enough to see the wear and tear on the shuttle’s nose. He sees the solid mother-and-child form nestled in scaffolding. Ultimately the hulking parent lofts the shuttle child off into space.

Chakeres sites the rockets precisely on the pad across perfect lagoons. After liftoff, he exalts. The camera chases the missiles into the sky, and the scene is enveloped in plumes of steam and exhaust.

Look at his portrait Challenger, Sunrise (1984). This ship is heroic; its iconic silhouette is kissed by a hazy, glorious ball of sun, a pink line of dawn along the horizon. Three decades after its creation, it is still a handsome tribute to the successes and failures of the shuttle program.

His Discovery Mission 51A - Pad 39A Remote Site 1, 1984, works as a striking counterpoint. The set-up is similar but what is still and quiet in the latter is here all force, with the combustion and exhilaration of lift-off, his “decisive moment” of exaltation.

The technical tour de force was designing a housing to protect the camera and building a remote mechanism to start the camera at the moment of launch. Preparation was building fail-safe camera systems to insure getting the picture. Creative vision was studying sun angles and knowing where the sun would be at the moment of launch, and placing the camera to get the most compelling image. And luck, having a storm front moving in at the moment of launch shrouding the scene in a dramatic grey background.[iii]

These are parts of a love story.

But tragedy struck again. Just before noon on January 28, 1986, astronauts were killed in flight for the first time. The NASA Space Shuttle Orbiter mission (the tenth flight of Space Shuttle Challenger) broke apart seventy three seconds after take off. All seven crew members perished, and nearly one in five Americans witnessed it on television.

John Chakeres was at the Cape and saw it in person. He and the astronauts’ families and President and Nancy Reagan watched as the spacecraft disintegrated off the coast over the Atlantic Ocean.

The explosion had a particularly devastating impact on Chakeres. He put away his work and didn’t look at it for almost thirty years. It was five years of material with thousands of negatives, and he set it all aside. It was not until the summer of 2013 that the photographer returned to it and began scanning the negatives and making prints. The good news is that, in the Space Shuttle project he found himself again spiritually: his creativity, his passion, and his fascination with technology as a means of fulfilling his vision; he felt whole.

It is more than ironic—and revealing— that a young man captivated by space travel and the systems for conquering it, fascinated by the idea of entering into the infinity of it, would then begin to work so differently. In the past dozen years, the artist John Chakeres has become best known for his color photographic studies of walls and doors, and their shapes and surfaces. Two dimensions.

His obsession with rockets and the beyond seems to have been sublimated or supplanted by a need to close himself off with barriers or walls, to literally shut the door on the kind of seeing with which he had been so consumed.

Chakeres dealt with his trauma artfully, consciously or unconsciously. He finds meditative primal force in his Grey, Structure, and Concrete series, “where order is beauty, beauty is order, and everything necessary to comprehend a given image is contained within the image.”[iv]

But going back to these “First Fleet” photographs from the 1980’s has been an act of redemption for the photographer. This work was something rare and special, even exalted. It is certainly worth the fresh look offered in this book.

In these Pre-flight photographs you can see Chakeres’ respect for the shuttle itself. His images of the shuttle don’t show a slick, idealized spacecraft, but, more simply, a good looking, massive and weathered machine—a noble machine.

After takeoff, in the series The Launch, the artist captures swirling and streaming clouds in a celebration of spiritual transcendence. Skies are darkened in the late afternoon, evening skies are deep black, and the only lighting is from the spacecraft.

The Landing images, the return to earth, are delivered in the light of an early morning, hopeful sun. All is calm. Return to ground control.

The last Shuttle mission took place in 2011. First Fleet is the artist’s “Rosebud,” a unique time capsule and testament to this Rocket Man’s love and healing as he returns to his experience of this special and shining moment in the modern era.

[i] Elton John and Bernie Taupin, “Rocket Man,” 1972. © Universal Music Publishing Group.

[ii] This line is taken from the opening voice-over for the 1960s television series Star Trek: “Space: the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise. Its five-year mission: to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before.”

[iii] Correspondence with the author, February 21, 2018

[iv] The artist, quoted from his website. http://johnchakeres.com. Accessed April 30, 2018.

John A. Chakeres, Discovery Mission 51A - Pad 39A Remote Site 1, 1984

John A. Chakeres, Challenger, Sunrise, 1984

John A Chakeres, Columbus, Painted Windows, 2008

John A Chakeres, Medellín, Museum Wall, 2014